Hero

Jonah Peretti: He was the least well-known of the four founders of Huffington Post 10 years ago. Jonah Peretti was a 31-year-old environmental studies graduate, who had taught computer science in New Orleans.

While studying for his MA at the MIT Media Lab in 2001, he had achieved accidental web fame. Nike was promoting customizable trainers so he ordered a pair imprinted with the word “sweatshop”. But Nike refused what it described as “inappropriate slang”, prompting an exchange of e-mails, which Peretti forwarded to 10 friends. It went viral and he found himself on US breakfast TV debating a Nike spokesman about its labour practices – and pushing his request for a picture of the 10-year-old Vietnamese girl who had made his trainers.

Four years later, pioneer blogger Arianna Huffington partnered with former AOL executive Ken Lerer to launch HuffPo. They hired Jonah Peretti who was described as “a viral marketing hotdog”. The site, which cost a mere $2m to launch, built an audience of 2m monthly uniques in its first year. In 2011, it was bought by AOL for $315m, but not before Peretti and Lerer had founded an “internet popularity contest” site.

That became BuzzFeed which quickly grew to become a web traffic behemoth. Last year, it secured £50m investment from Silicon Valley investor Andreessen Horowitz, valuing the company at $850m. It is now worth more than the £1bn which would-be bidder Disney balked at paying a year ago.

Its early popularity was based on listicles (a cross between lists and articles), pictures of cuddly pets and news-you-can-share. But, this week, BuzzFeed was described by The Atlantic as “the most influential news organization in America”, the successor to previous generation-shifting media like Time magazine, USA Today, CNN and MTV.

BuzzFeed now has more than 900 employees in 10 offices around the world. It gets 200m unique visitors and 1bn video views a month. It has reportedly been profitable for almost three years. Its financial success – ahead, for example, of the UK’s similar scale Daily Mail Online – is based on its mastery of digital media and ‘native advertising’. It is, quite simply, streets ahead in monetising audiences on the smartphone screens that are still torturing traditional media companies, spoiled by decades of big-space display advertising.

From the start, Peretti was committed to building a “global technology platform” and designed BuzzFeed as a “free, open platform for launching ‘buzz’ ”. He saw it as “a one-stop shop for web ‘buzz’: editorial, algorithmic, user generated…able to dramatically grow traffic without hiring editors”. (He then had just two journalists). And, here in 2010, is the first known reference to “native” advertising: “BuzzFeed partners can publish and promote their buzz on the BuzzFeed site. The promotion is native to the site and works as content and advertising.”

To media traditionalists, BuzzFeed is a mass of contradictions: a journalism website, a purveyor of funny lists, and a perpetual pop-culture ballot box where you can vote on articles with bright-yellow lol, wtf, and omg buttons. It is increasingly also the home of serious news by first-rate journalists. The serious side came when Peretti hired Ben Smith as editor in chief in 2012. The US political journalist and blogger – who recently interviewed President Obama on video – took BuzzFeed deep into the news business. Today, he has a team of more than 150 journalists, including star recruits from the Financial Times, Washington Post, Propublica, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, Village Voice, Rolling Stone and Gawker. And they’re increasingly all over video and podcasts.

Gawker Media founder Nick Denton long ago predicted that BuzzFeed would “collapse under the weight of its own contradictions” and he must have had a wry smile at a little recent difficulty it faced for pulling articles from the site, allegedly because they offended advertisers. Whatever, the whole story, it was another reminder of the challenges that, inevitably, face advertising-funded free media. Judging by the recent fuss in London when the Daily Telegraph online reportedly did something similar, these controversies will keep coming.

But BuzzFeed is much more cool with another issue that also exercises traditional media: the distribution of content to sites like Facebook, SnapChat and LinkedIn over which the publisher has no control. BuzzFeed’s mastery of native advertising drives its ambition to publish as widely as possible on other sites and services. And instead of trying to use the likes of Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest to send visitors back to BuzzFeed, it is now happy to have its content – and its commercial messages – live beyond its control.

This “white labelling” is, of course, the very antithesis of conventional web, let alone print, publishing which says that you want to keep as many viewers as possible on your branded platform so you can maximize advertising revenues. But it’s the way the world is going. Snapchat’s new Discover platform, for instance – which has captured the imagination of both publishers and advertisers – doesn’t send any outbound links to content providers. And Facebook is talking to publishers, many of whom are agonising about whether to supply their content for its news feed. Many of the long-time emperors of news are finding it difficult to face up to a world where they are, well, less important – and where they find it impossible to apply their traditional revenue-generating skills.

Peretti’s motivation is clear. In January, BuzzFeed received a no-slouch 420m views via referrals from Twitter, Pinterest and Facebook. But it generated a mighty 18bn impressions actually on those platforms. That is the commercial potential it is now seeking to exploit.

So, once again, you have the picture of a live-wire new media company growing and changing in ways that torture traditional media. As Peretti told his team in an email last month: “Time (magazine) began as a clipping service in a small office. A group of writers subscribed to a dozen newspapers and summarized the most important stories, rewriting the news in a more digestible format. BuzzFeed also started as a clipping service in a small office seven years ago. Instead of subscribing to newspapers, we surfed the web (and used technology) to find the most interesting stories and summarized them into a more digestible format.”

Jonah Peretti is “convinced we’re at the start of a new golden age of media and that BuzzFeed will have a big role to play.” Who would doubt it?

Context: How BuzzFeed will become world’s largest news service

Villain

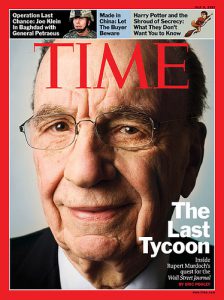

Rupert Murdoch: For all his resourcefulness, far-seeing strategy and global success, it’s just too easy to tag the Aussie-born, American master of world media as a “villain”. Brits have seen him and his executives effectively on trial, and Australians recently accused him of avoiding taxes. James Murdoch’s “didn’t read it” defence

against 2012 charges of cover-up has reportedly not deterred his father from planning soon to install him as head of 21st Century Fox. No sooner had the UK courts simultaneously started to throw out recent phone hacking cases against his journalists and step up prosecutions against the rival Daily Mirror’s own hacks than election reporters turned to focus again on Rupert Murdoch himself.

The News Corp / Fox boss, who famously told a judicial inquiry that he was far too busy to make regular calls to newspaper editors, was in London just before his 84th birthday. He took time to meet Conservative politicians and to berate executives on strident tabloid The Sun for not doing enough to ensure that Labour, led by Ed Miliband, does not win the UK general election. He reportedly warned them that a British Labour government would try to break up News Corp, which also owns The Times and The Sunday Times.

He apparently instructed his editors to be much more aggressive in their attacks on Labour and to be more positive about David Cameron’s ruling Conservatives in the run-up to polling day, on 7 May. Two days later, The Sun devoted a two-page spread to the election. On one side was a 10-point “pledge” to voters by Cameron and, on the other, an attack on Labour, “quoting” its finance spokesman: “I ruined your pensions, I sold off our gold, I helped wreck [the] economy, Now I’m going to put up your taxes.” This was the familiar picture of Murdoch’s media with the gloves off. It is, after all, a full 36 years since a British

government has been elected without the support of Rupert Murdoch. That does not mean that he won each battle, of course. But it does mean that politicians have consistently feared that his power may possibly be decisive, and so they play safe with him.

They are haunted by famous headlines like “It was The Sun wot (sic) won it!”. But, perhaps, these can now be seen as the high-water mark for a newspaper whose fortunes had been transformed in the 1970s by editor Larry Lamb who once quoted Murdoch’s instructions as: “I want a tearaway paper with lots of tits in it”.

The paper, complete with its infamous “Page 3” nude women, stormed through the 1980s and 1990s and became (by far) the UK’s biggest-selling and most profitable newspaper. The “Soaraway” Sun delivered power and profitability in equal measure to the burgeoning News Corp, with annual operating profits reaching £80m. It also helped the company to stomach the perennial losses of The Times in London, The Australian, and the New York Post.

But things have changed in the country whose former prime minister Tony Blair once flew half way round the world to secure the support of Rupert Murdoch and his newspapers. After months of tabloid attack on Labour, the opinion polls have scarcely moved.

The race is still too close to call – despite David Cameron’s apparent tailwind of economic recovery. The decline in media’s political clout is hard-baked by a fast-growing and hard-to-reach millennial audience that consumes much of its news through social media – and a UK political class that is not very digital. The erosion of press power is characterised by the decline of what was Europe’s second largest newspaper. The Sun is estimated now to be selling some 1.6m copies daily – less than one-third of its 1990s peak – and with profits down by more than 60% to, perhaps, £30m.

It has taken a determined election effort by Murdoch’s once so-powerful tabloid to prove that, even in a UK news market long-dominated by its clutch of legendary national dailies, newspapers are not what they were. And nor are their proprietors. Happy Birthday, Rupert.

Context: Who will win the global news race?